Resources

A Playwright’s Autumn in Literary Company

Chan Ping-chiu, The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Fellowship Writer

‘Light and dark – it’s not that I choose one or the other, but that the light turns to dark and the dark to light. Every moment, I remember this.’ – A Red Flower Falls in Autumn, Chan Ping-chiu

Chan Ping-chiu is a theatre veteran. In addition to having directed a number of acclaimed stage productions, including The Phenomenon of Man: Revolver and Der Goldene Drache, he has penned plays such as Best Wishes and Tête-bêche, which are responses to Hong Kong society. He also serves as artistic director of the On & On Theatre Workshop. On & On is a rare phenomenon in Hong Kong, being one of the few theatre companies to have its own performance venue. The company has proven to be both bold and innovative in its use of space, theatrical forms and exploration of dramatic texts. Last year, Chan Ping-chiu was the first Hong Kong playwright to participate in The University of Iowa’s International Writing Program (IWP) in more than a decade.

The Origins of the International Writing Program

The University of Iowa’s International Writing Program was officially established in 1967 by poet Paul Engle and Chinese novelist Hualing Nieh. Each year, writers from around the world are invited to Iowa to engage in exchange and to write. During the Cold War, the IWP was that rare place where writers from across the Chinese diaspora could gather. Over the years, many Hong Kong writers have received invitations to participate. Early on, these writers included Dai Shing-yee, Koo Siu-sun and Lee Yee. Other famous Chinese participants include Lin Hwai-min, Wang Anyi, Feng Jicai, Yu Hua, and Mo Yan – all well-known names.

The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation has sponsored Hong Kong writers in the IWP since 2009. In the past decade, Dung Kai-cheung, Hon Lai-chu, Dorothy Tse, Chan Chi-tak, Lee Chi-leung, Tang Siu-wa, Matthew Cheng, Virginia Suk-yin Ng, Stuart Wai-shing Lau and Chow Hon-fai have been IWP participants. Last year, playwright Chan Ping-chiu and poet Chan Lai-kuen joined their ranks.

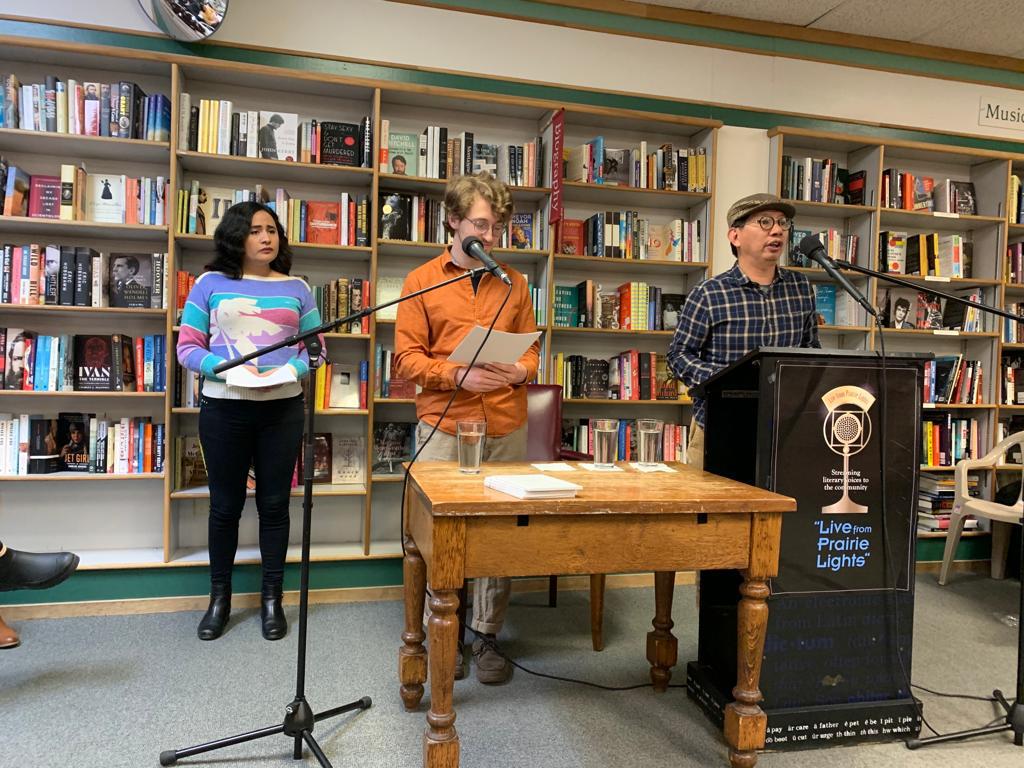

‘I invited a Mexican writer who’s also an actor to take a role… I also looked up a local friend, and with the addition of myself, we did a three-person reading.’

A Playwright in Iowa

Chan Ping-chiu is active mostly in theatrical circles, so the trip to Iowa was a very different experience for him. ‘Initially, I thought I would be out of place in the IWP because my focus isn’t on writing. When I got there, I found that quite a few of the participants did something besides write. One was a film director. Someone else was an actor.’

The IWP is held every autumn for a period of two and half months. In 2019, writers from more than 20 countries were invited to Iowa.

How a writer shares creative work inevitably depends on what type it is. A poet or novelist can share poems or part of a novel by giving a reading, but how does a dramatist stage a local performance of his work? Chan Ping-chiu described the program’s requirements: ‘The program’s pre-departure instructions let us know we’d have three key exchange obligations. The first was to teach a literature class, the second was to participate in a panel discussion, and the third was to give a reading of our work.’ For his reading, he didn’t simply read aloud from the prepared chap book of his work, which had been printed with parallel Chinese and English texts. Instead, he chose to give a dramatic reading for a group of Iowans.

A Dramatic Reading: a Response to a High-Culture Tradition

Smiling, Chan Ping-chiu explained that a dramatic reading can have many forms. It can consist of one person reading, or many, and the reading style is flexible. ‘I invited a Mexican writer who’s also an actor to take a role and taught her the song “Kowloon, Kowloon Hong Kong”. She was a quick study. I also looked up a local friend, and with the addition of myself, we did a three-person reading. The reading included my 2018 work Tête-bêche and the short play A Red Flower Falls in Autumn, which I finished writing late last August, before I left for Iowa.’

While the writing program was in session, Iowa City overflowed with festive energy. As a group, the writers visited a farm outside the city, received invitations to eat with locals and participated in various literary events. Travelling back and forth to the downtown area, Chan Ping-chiu was surprised by Iowans’ appreciation for public readings. ‘In addition to the Book Fair, there were some people performing a marathon reading of War and Peace, in nearly zero-degree weather. No one gave them weird looks. Passersby would nod in greeting. We don’t see many high-culture traditions like that in Hong Kong.’

A Symbiosis of Literature and Dramatic Texts

According to Chan Ping-chiu, the IWP has changed over the years, gradually reaching the point of encouraging writers to interact more and immerse themselves in their work less. ‘Writers from more than 20 different places were gathered together, producing a chemical reaction that resulted in something like a celebration. When they’re on their home turf, writers inevitably form cliques and disagree about artistic ideals, but at IWP, no one argues about things like that. Despite differences in age and literary status – some writers already have significant reputations, and others are just getting started – no one made any distinctions in the IWP. The extroverted writers in particular were quick to get acquainted. The writer from Nepal runs a literary festival. He often joked that he was going to invite all of us writers to the Nepal Literary Festival.’

As the artistic director of a theatre company, Chan Ping-chiu had a similar idea. ‘The Mexican writer and the Latvian poet I got to know at IWP both have work that would be suitable for a stage production. If On & On could invite them to Hong Kong for some smaller projects, that would be very interesting.’ He mentioned that there have been various ongoing attempts to bring theatre and literature together in the past ten years or so, but that developments in theatre happen too quickly. There isn’t enough time for the dust from these attempts to settle.

Chan Ping-chiu summed up his observations about theatre and literature this way: ‘Theatre tends to emphasise interaction – immersive theatre and documentary theatre are both good examples of this – to the point that it’s transformed into an event. But we must absolutely never forget that theatre has its roots in written texts, and there’s still lots of room for theatre based on that tradition. I believe literature has remained a pure artistic experience in a complicated world. That’s something irreplaceable for theatre.’